A month without R# or Rider - Editing, Debugging & Refactoring

What was this about again?

This is part 2 of my experiment to use a plain Visual Studio 2019 for a little bit more than a month. In part 1, I talked extensively about the rationale for this and focused on the general usability aspects of Visual Studio and Rider and navigating through your code-base. In the second part, I’ll dive into the editing, unit testing and debugging experience, talk about some of the things Visual Studio does better and share my final conclusions.

Editing

A lot of developers believe that the most important thing of their job is to produce code. We all know that our job is much more complicated than that and thinking about solutions, talking to the business, and explaining our direction is equally as important. Nonetheless, editing code still takes a sizable chunk of our day-to-day job. So the first thing I noticed after finding the file I was interested in, was that code in Visual Studio looked a bit pale. At first, I thought that it didn’t color the code as explicit as Rider.

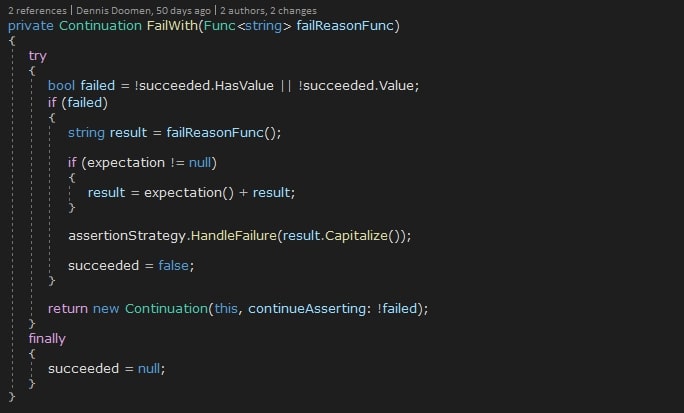

Now compare it with Rider (in its dark mode).

So at first glance, the difference isn’t as big as you may expect. Visual Studio highlights local variables, whereas Rider does this with fields. I do like how Rider always shows you the name of the parameter, even though I know not everybody agrees with me on this. And did you notice how Rider shows the return type of a chained API?

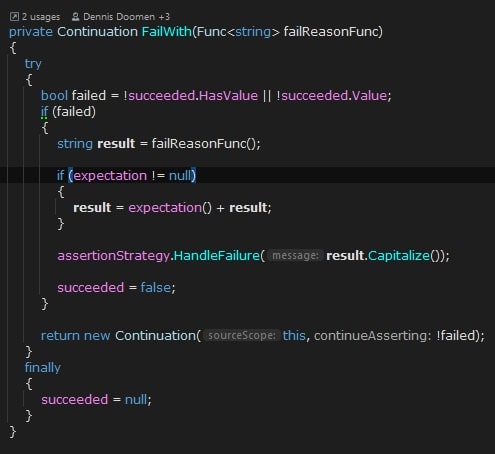

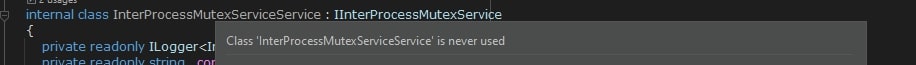

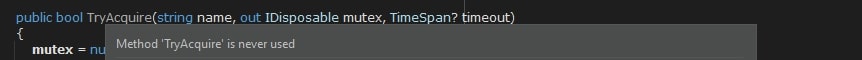

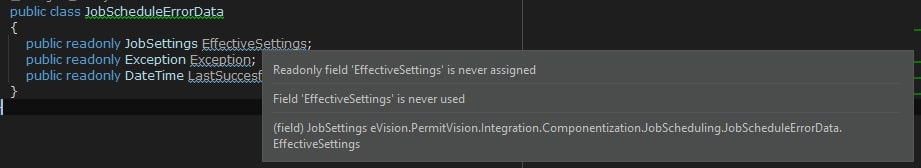

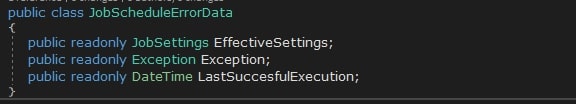

But the real killer feature that I’m missing in Visual Studio is Rider’s ability to perform a continuous code analysis. This will surface all kinds of design, coding and style issues, and can be extended with custom Roslyn analyzers as well. For example, here is a snapshot of some of the rules Rider verifies for you.

You can even extend this with a solution-wide analysis. This will extend the potential code issues with detection of unused classes and members, constructors that are never invoked, members that are protected, but never overridden and all kinds of other problems. You can even annotate your code with (dependency-free) attributes to help the analyzer understand that your public method on that public class really is designed to be public. Enabling solution-wide analysis is a great way to get rid of dead code easily or to get more control on what your project is exposing to other projects.

Now compare this same class with what it looks in Visual Studio:

With a past of RSI complaints, I’ve taught myself to prefer the keyboard over a mouse as much as possible. It doesn’t mean I don’t use the mouse at all or prefer to use CLI interfaces only, but merely that I rely a lot on keyboard shortcuts while editing my code. Something that I immediately noticed is how Visual Studio handles selecting an identifier written in Pascal or Camel casing, or more precisely, how it does not handle it. Rider has a built-in feature called Camel Humps that allows you to expand the selection by the parts of the words that are delimited by different casing or an underscore. It’s small feature, but really noticable if you’re used to it. And Rider takes this quite far. For instance, searching for a method like SelectFirstElementOfCollection can be achieved by typing SFEOC (or the first part of it depending on the uniqueness). But also double-clicking an identifier will start selecting the chunk of the identifier that the cursor is on, and then expands to the chunks around it.

Talking about expanding a selection, Visual Studio isn’t as smart as Rider on that part either. When your selection reaches the edges of a method, VS first includes the braces of the entire body, then the method definition itself, but then somehow does not stop at the XML docs. Instead, it expands the selection all the way to the adjacent member. So duplicating an xUnit test case as a starting point for the next one is a little bit more work. But when you finally managed to select the entire member including its XML docs, and try to use keyboard shortcut CTRL-ALT-SHIFT-UP/DOWN, instead of moving the entire member above or below the adjacent member, you’ll discover that VS will just move it one line up or down.

Quite often it’s all about subtle details. For instance, when you need to provide an argument that takes an interface or abstract class, Rider will suggest all implementations of that interface. Visual Studio does not do anything.

Refactoring

If you have followed the development of the C# language, you may have noticed that it’s not always obvious which feature is available in which specific version of the language. Don’t you remember reading about some cool new upcoming language construct in some blog post, and then losing track of which version it became part of eventually? This is why I loved ReSharper (and now Rider) so much. It will regularly remind you how some code construct can be replaced by a newer and potentially more concise language feature. For example, if you use private set on a property, Rider will suggest you to remove it. Heck, this is how I’ve been learning new C# features in the first place. Here’s an example from Visual Studio:

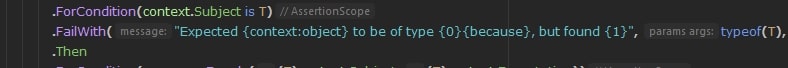

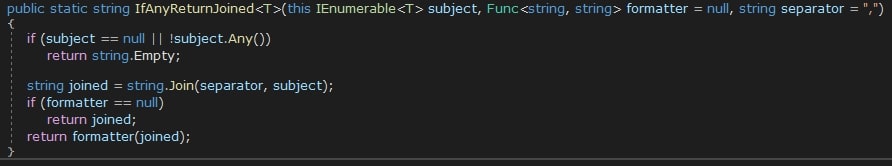

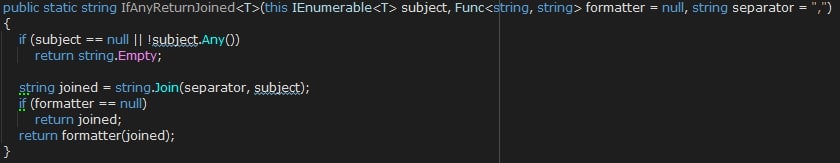

Now compare this to what Rider tells you:

The greyed out method name indicates it is never used within the entire solution. The underlined subject parameter will tell you that the IEnumerable<T> is being enumerated multiple times. It also suggests to replace the string joined declaration with var joined (although that’s a taste thing), and it suggests you to replace the last if statement with a conditional return.

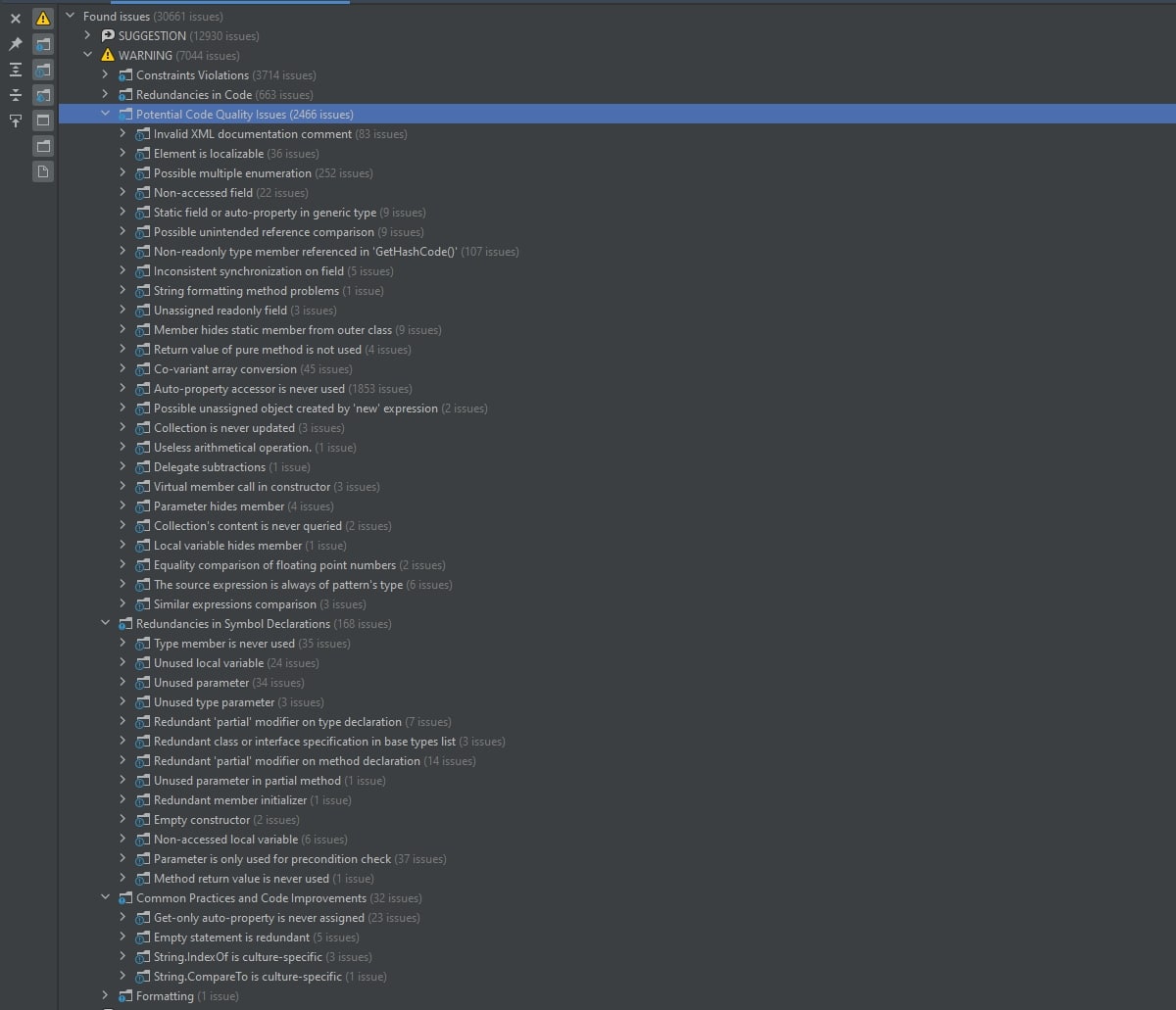

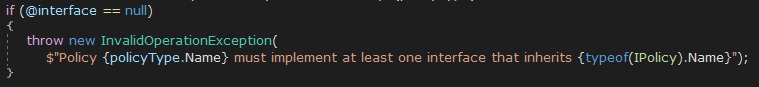

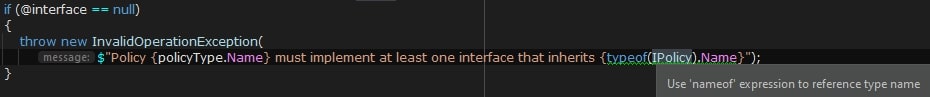

Here’s another example from Visual Studio:

This is what Rider tells you:

Whenever Rider underlines some code with those colored squiggles, you can press ALT-ENTER to show the most applicable quick fixes in a pop-up. Visual Studio also has some of these available, but as you’ve seen earlier, it doesn’t tell you about. Also, Rider has some extras that Visual Studio doesn’t offer either.

- Changing a mismatched type of a parameter from the call side

- In-lining a

letvariable inside a LINQ statement - Convert a LINQ query into a method statement

- The

foreachauto-complete starts with the collection type instead of first choosing the collections - Renaming all non-existing symbols to something else on member or file scope

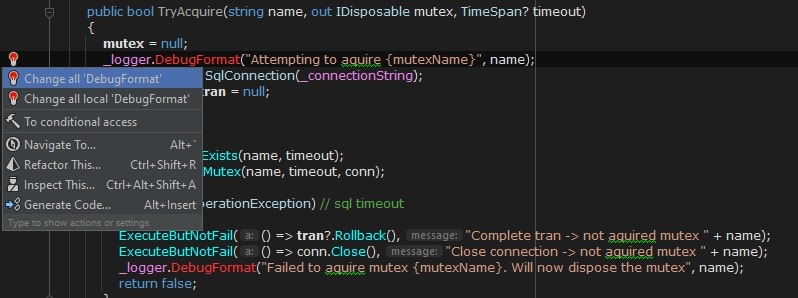

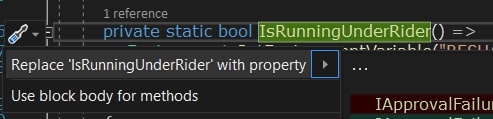

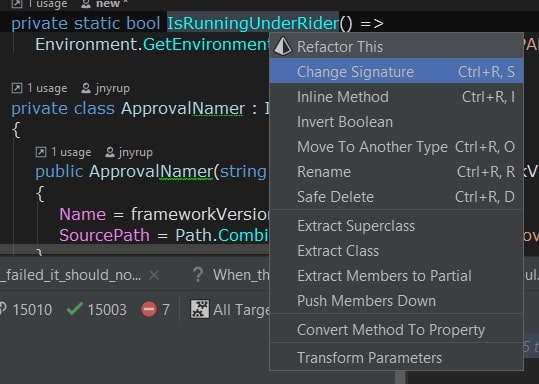

Less critical but slightly annoying is that a lot of refactoring options are only available from the implementation of the target. E.g. converting a method to a property cannot be done from the calling side. But even then, the difference is noticeable. For instance, check out Visual Studio’s suggestions.

And now Rider’s list of refactorings:

There are tons of more refactorings that I’ve been taking for granted over all those years, and barely any found their way to Visual Studio. You can find the full list in the Rider documentation.

It’s not all bad news though. I really like the pop-up preview window for quick-fixes that Visual Studio offers. And for many warnings (such as using the wrong overload), it will open up an explanation page. Even though both Visual Studio and Rider provide plenty of quick-fixes, Rider doesn’t provide this kind of useful documentation.

Unit testing

I’m a strong proponent of automatic testing and totally feel uncomfortable changing code without first writing tests. It’s almost like driving without a seatbelt (which I never do). In other words, the unit testing experience is very important for me.

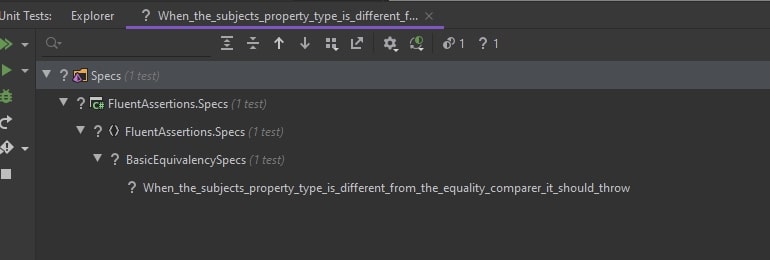

The first thing I noticed after opening a file with xUnit tests, is that Visual Studio did not detect them right away. At first I thought it was a glitch, but some times, after minutes of waiting, it still did not mark that method as a test case. This was particularly annoying when you add new tests to the file. Opening the Test Explorer window did often help.

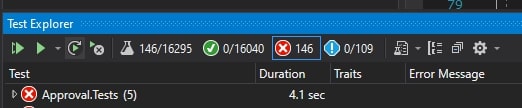

Running the almost 16K unit tests in FluentAssertions takes less than 30 seconds in Rider, but at least a minute in VS. I’m not sure if this is caused by Rider’s default multi-threaded execution of tests, something you have to enable explicitly in VisualStudio by fiddling with a .runsettings file. Checking the Enabling Run Tests in Parallel setting reduces this to about 50 seconds. However, I’ve observed long freezes in the progress bar. Almost as if there’s some kind of lock contention. For reference, I’m running this on an HP all-in-one machine with a Core i7-8700T and 16GB of memory.

Another annoying thing is that there’s no way to run all tests inside a class or within a specific scope. You can only run multiple tests by selecting them from the Test Explorer or running individual tests using the icons in the gutter. And talking about usability, if you have a couple of failing tests, clicking on the button that shows the number of failed tests will hide the failed tests from the results instead of showing only the failing tests. In Rider, this works as you would expect.

Even though I’m using xUnit everywhere, I do see some differences in behavior between Visual Studio and Rider. For instance, if a test throws a StackOverflowException, the test just fails with status inconclusive in Visual Studio. You have to dive into the details log from xUnit in the Output Window to figure out that it was a stack overflow problem. The same test in Rider just fails with the StackOverflowException in the test output.

When you’re debugging a unit test, there’s no way to easily find that test in the Test Explorer, nor the ability to create a new Play List (or Test Session in Rider). Quite often I group a couple of related tests to work on them. And when you start diving deeper in the code, it’s quite difficult to find your way back to the original test.

Also, Visual Studio has no way to keep running/debugging a test until it fails, which is particularly handy for brittle tests. On the other hand, I do like how Visual Studio shows the output of a unit test as a popup next to the test code itself. And it feels like the time to start debugging a unit test is slightly faster in Visual Studio as well.

Debugging

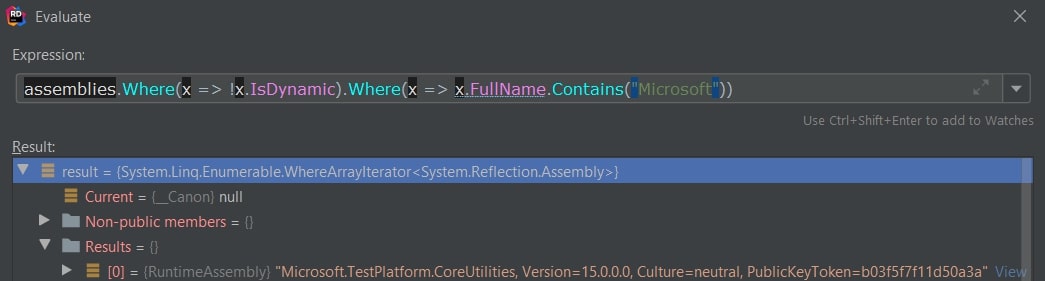

Talking about debugging, I always thought that Visual Studio’s Immediate Window was one of the crucial features Rider was missing. However, I recently discovered that Rider’s Evaluate Expression pop-up supports building dynamic LINQ statements. And you don’t need to worry about namespaces or anything like that. Since this was a feature I was expecting Visual Studio to add years ago, that was a happy discovery.

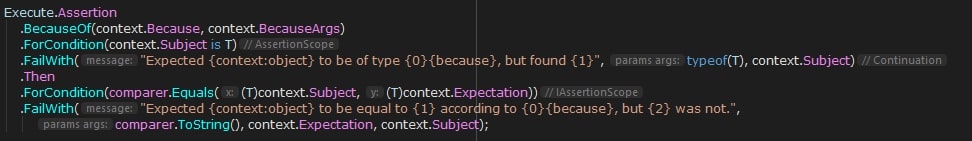

Visual Studio misses a lot of the features of Rider for stepping into and over lines of code. E.g. it does not allow you to continue the debugger until the line you’ve selected while ignoring any breakpoints. But it also does not know what to do with a multi-line chained or nested call such as in the below screenshot.

If you set a breakpoint on this block and tell Rider to step into this, it’ll allow you to choose which part of the chained call you want to step into. Visual Studio will just select the entire block and execute it as one block.

Debugging external libraries is also impossible to do in Visual Studio. As I mentioned in the previous post, Rider can decompile any external code using it’s built-in version of dotPeek. But that’s not all. You can even set a breakpoint on a decompiled member, and everything works as expected.

Visual Studio has had breakpoints that only trigger based on a certain condition for years, but it’s still tied to a specific line on which you put your breakpoint. Rider supports all of that, but also supports a special kind of breakpoint called a Data Breakpoint that triggers when the property of a specific object changes its value, irrespective at what lines.

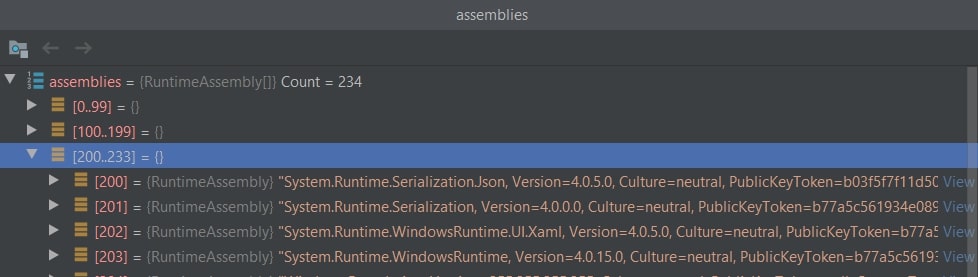

While inspecting a collection object with a lot of values, Visual Studio just creates an everlasting scrollable list. Rider will create a hierarchical view that makes it easier to navigate through.

And when you want to continue inspecting a specific instance, which itself could be a collection, you can click the icon on the top left to focus it on that item and continue drilling down, or use the arrows to browse back and forth to return to a previous point.

What else is missing in Visual Studio

In addition to the things I’ve mentioned up to this point, here’s a list of other features I was missing during my experiment.

- Rider has built-in code coverage and semi-automatic testing (after saving or building). Now, Visual Studio users can get a license for NCrunch, which is superior to anything I’ve seen before.

- In Rider, you can compare your selection with the clipboard, or launch a fresh new empty comparison from inside the IDE.

-

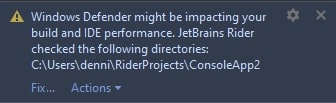

If you have a virus scanner running, Rider will suggest a quick-fix to exclude certain directories from the scanner.

- Since I regularly share code as part of a conference talk or training, I love the ability to quickly switch themes without having to dig through pages of options as well as use Rider’s presentation mode.

- Both Visual Studio as well as Rider allow you find options using a keyboard shortcut, but Rider allows you toggle options right from the search results.

- Visual Studio has tooltips for its buttons, but Rider also provides a more extensive explanation of that button in the status bar.

So what’s the verdict?

I really tried to give Visual Studio the benefit of the doubt. As I started my first post, I heard some really good stories about Visual Studio from people in the community and with the OPEN development of .NEt 5, Microsoft clearly showed that it has its heart at the right place.

But all in all, I can’t ignore the fact that Rider is miles ahead of Visual Studio. And not just that, the distance is increasing release by release. The whole package is just much more complete than Visual Studio, not only on features like navigation, editing and debugging, but even more on the refactoring side. The overall UI experience is very mature and clearly has been optimized for years, with great support for keyboard users, a low memory footprint and excellent responsiveness. So if you care about your productivity and want to avoid frustration, switch to Rider and never look back.

Fortunately my employer and clients I work with understand this too and usually offer JetBrains licenses to all their developers. But even if this would not be the case, I would probably buy one myself, or make sure I get an open-source license. Even in 2020, it’s pure frustration to work with Visual Studio without ReSharper or Rider.

So what do you think? Do you have similar experiences? Or do you not see the added value of any of these tools and remain with a plain old Visual Studio? Let me know by commenting below. Oh, and follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for suggestions and ideas to become a better professional.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment