16 practical design guidelines for successful Event Sourcing

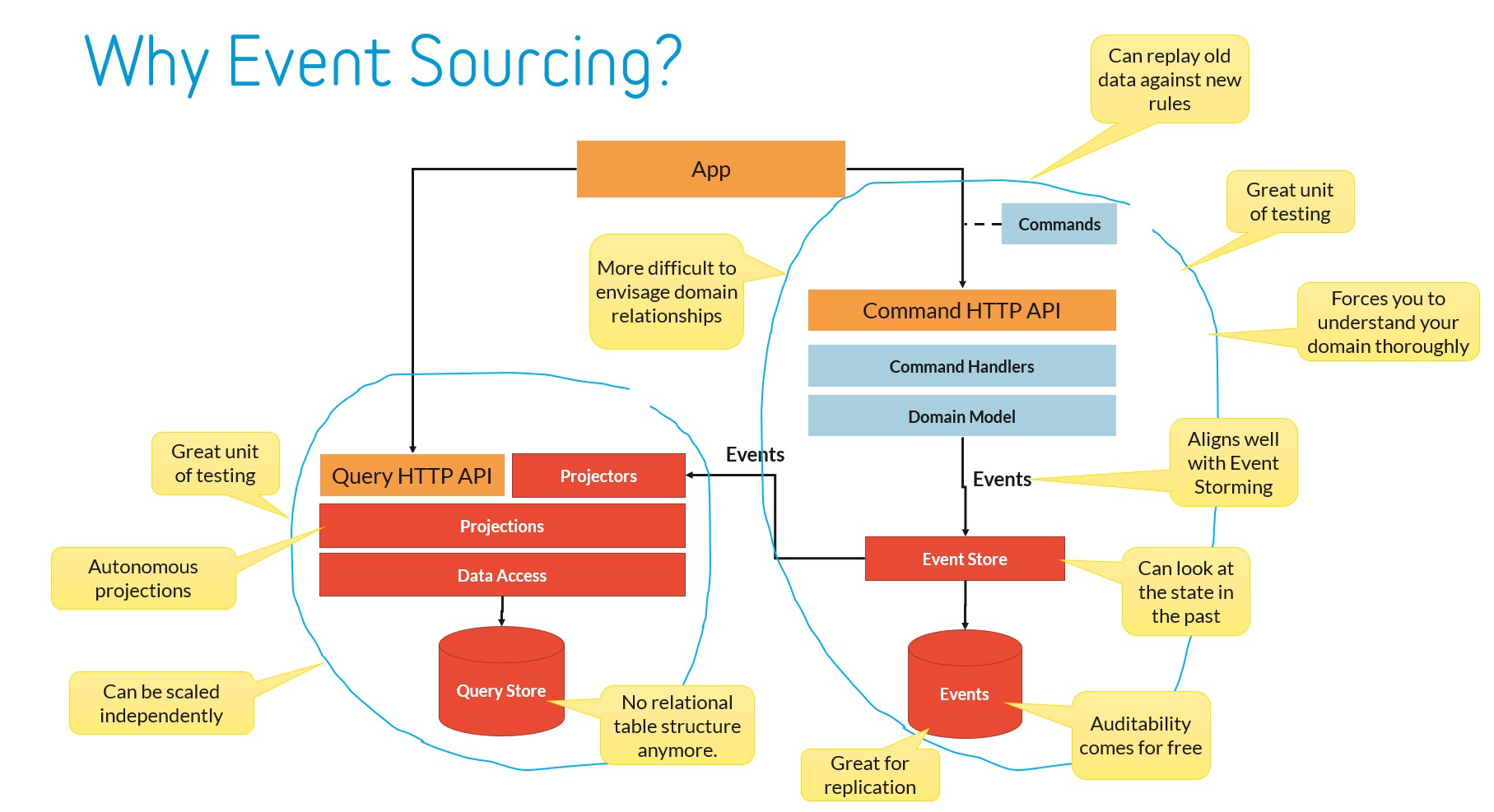

A couple of weeks ago I ended up in a technical debate on how to take an existing Event Sourced application further to fully reap the benefits it is designed to give you. I’ve written many posts about the pitfalls, the best practices and how to implement this in .NET specifically. But I still thought it might be useful to provide you with a list of the most important guidelines and heuristics that I think are needed to be successful with Event Sourcing.

Don’t use Event Sourcing unless your domain needs to capture facts or decisions or has to deal with a high degree of user collaboration. You don’t need Event Sourcing just for building an audit log. And even if you do use Event Sourcing, you may not need it for everything. Quite often, master data can be handled using versioned schemas just as well. But then again, for smaller teams, having a single paradigm might be better. But don’t ignore NoSQL as an alternative to Event Sourcing.

Do model your aggregates around invariants instead of business concepts or data oriented. But be careful that you choose which invariants the aggregate must protect and which of them can be resolved using a more functional approach (like optimistic concurrency or compensating tractions). If you don’t, you’ll end up with a monstrous aggregate. Vaughn Vernon’s 3-part series called Effective Aggregate Design dives into that.

Don’t be dogmatic about cross-aggregate transactions. Only if you really need the performance and concurrency, force yourself to only touch one aggregate per transaction. Otherwise keep it pragmatic. The complexity of protecting cross-aggregate business rules without the transaction logic can be quite challenging and is usually not worth it.

Do assign a (natural) partition key to each aggregate, so that if you ever need it to split your event store because of performance or storage concerns, you can.

Do treat the event store as one big audit log of what happened in the business and never change or reorder events. Ensure that you can unambiguously point to a place in the event store and see which events happens after that check point number. This can be of good use for distributed event store and blue/green deployments with incremental data migration. But being able to diagnose a production issue from the event store has been crucial to us over the many years we’ve been using Event Sourcing ourselves.

Don’t treat events as a way to capture property changes. This so-called property-sourcing is a smell that is often seen when the developers treat Event Sourcing as a technical solution without thoroughly understanding the business domain and/or involving people from the business. Consider using Event Storming or Event Modeling as techniques to map out your business process instead of focusing on data models.

Don’t use the domain events as a communication mechanism between domains or services. Event Sourcing is an implementation of a specific domain (or bounded context in DDD terms). Use more coarse-grained events for inter-domain communication, for instance by projecting the domain events into higher level events that are pushed to a message bus or API gateway.

Don’t change the events just to optimize the projection speed. The whole point of CQRS is that you separate the conflict of interest between the command side (the domain) and the query side (the projections). The aggregates and events change when the business domain changes. The projections change when the display/query needs change.

Do be explicit about what information you want to keep in events based on functional requirements. So if you need the full name of the user that signed a document at the time of signing, make it part of the event. If you just need the latest full name, project the relevant events.

Do give events unique identifiers and use that to associate individual projections with the latest event that was used to update. It is great for diagnostic purposes.

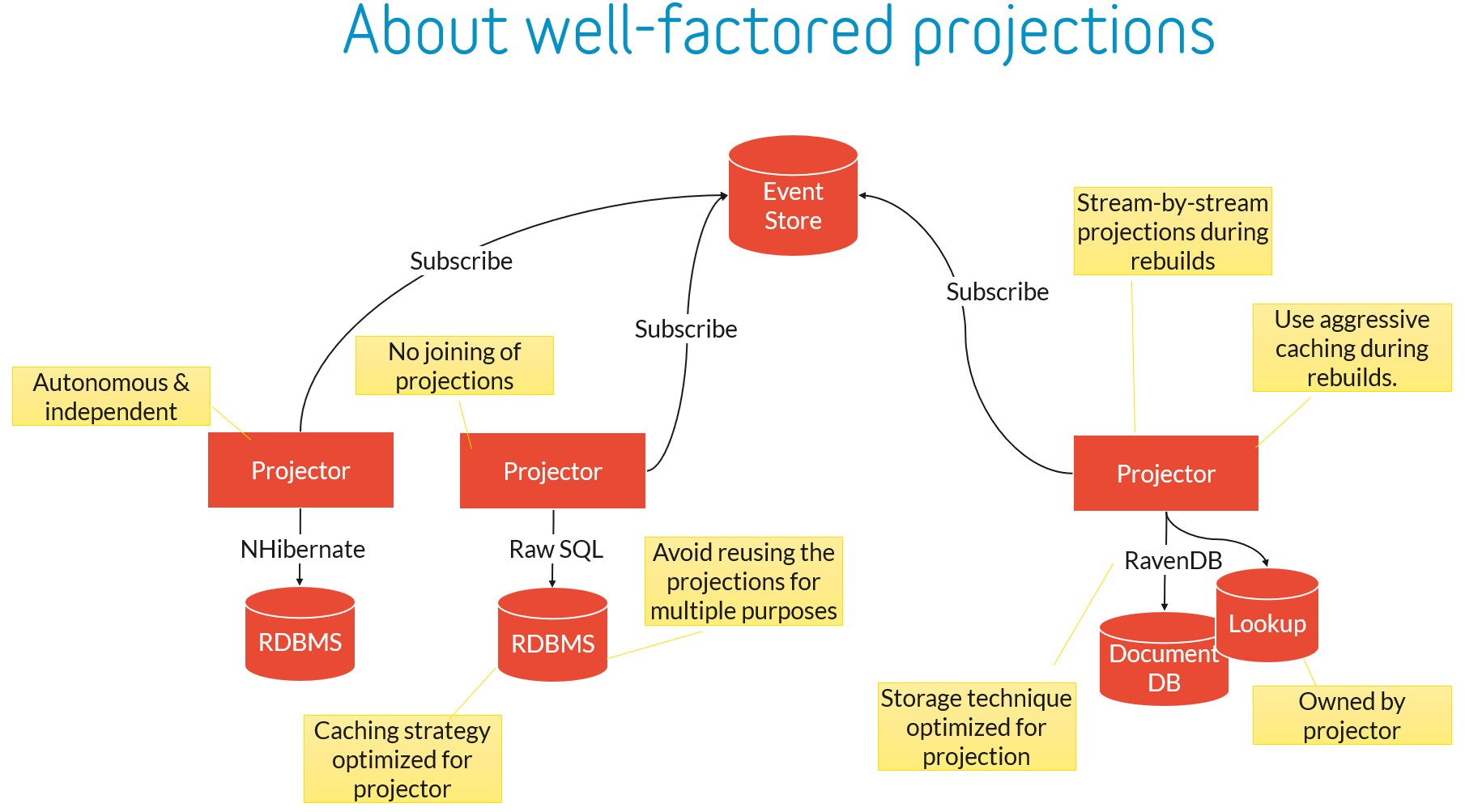

Do use autonomous asynchronous projections by default. Yes, it may add complexity to the UI to deal with the eventual consistency of the projection, but will open up a host of options that you will need to optimize for performance. Use whatever storage mechanism is fit for purpose, rebuild when you need to and, scale out projectors over multiple servers to gain top-notch performance. If you really need a specific projector to be updated as part of a domain change, consider waiting for the projector to catch up with that last event the domain issued.

Do be careful that under load, queuing the SQL-based event store based on a global check point might cause you to miss events due to in-flight transactions. Use a back-off window or serialize writes to the event store per partition to work around that.

Do treat rebuilding a projection as a special state by having the projector mark itself as being rebuild and expose its progress as ETA and such. A smart projector also detects if the event store was rolled back to an earlier state (because of a database restore or a production patch), and will rebuild itself automatically.

Do whatever you can to make rebuilding fast. Use aggressive caching, use a NoSQL database, project in-memory and in batches and then write to the database, project stream by steam if that makes sense for the projection, read from the event store in batches (and be smart about exception handling), use an ORM and benefits from its unit of work to reduce SQL statements, anything. You can even stop projecting events for aggregates that are no longer relevant for that projector, for instance, by adding metadata to the event store that all events of a particular aggregate (stream) are archivable.

Don’t join data from multiple projections, unless you know that this is safe considering the actuality and asynchronicity of each projector. If you do need to capture information from other aggregates, have the projector that owns the projection maintain its own private lookup based on the events of those aggregates. Another example of an exception would be the case where you build a data warehouse from your events, but even then you need to consider the trade-off of consistency.

Do test the entire projector as a unit of testing, with events coming in and query results or HTTP APIs as output. Treat the projector itself and the way it stores its projections as an implementation detail that can change over time. See an example of how to build such a test in a functional and readable way here.

So what do you think? Do you agree with these guidelines, or are they too dogmatic for your taste? Do you have something to add that I might have missed? Let me know by commenting below. Oh, and follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for suggestions and ideas to become a better professional.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment