Don’t blame the dependency injection framework

Over the last couple of months I’ve heard and read quite a few statements that say that Dependency Injection frameworks are bad things that you should avoid like the plague. In my opinion that’s just a result of rejecting something because it has been misused too long. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve been using them for years and fully acknowledge the consequences of misusing those frameworks and the effect on your code base. However, I’ve also learned that every tool has advantages and disadvantages. Knowing its strengths and weaknesses is part of the job of being a professional software developer. Dismissing a tool because of the latter seems a bit ignorant to me. So let’s talk about where this is coming from.

Why do people use them

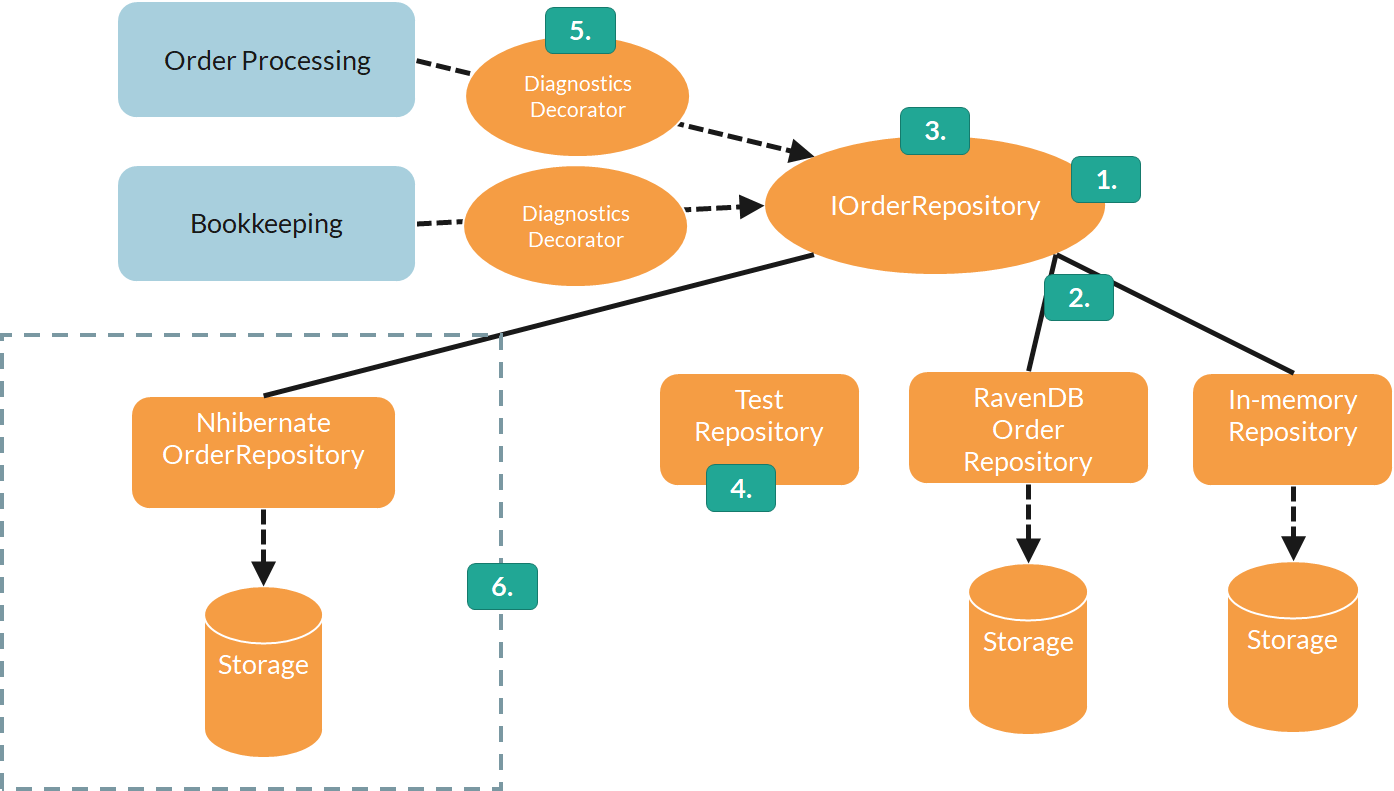

Consider the (contrived) diagram below.

In a design like this, I can think of several reasons why developers decide to use a dependency injection framework. For one, they may want to promote developers designing their classes in such a way that they only depend on abstractions (1). This is a good thing in my opinion, since depending on things that are more stable helps prevent the ripple effect. And since an abstraction is more stable than an implementation, we’re good. A nice side-effect of all of this is that it allows you to switch out one implementation with another (2), also known as the Strategy Pattern. This works particularly well if you need to have your unit tests work against a test-friendly implementation (4) of that abstraction. And don’t forget a system that likes to dynamically load implementations (a.k.a. plug-ins) from external modules (6).

In most real-world designs, different implementations of different abstractions are governed by different life-cycles (3). This is where a dependency injection framework can shine. They give you a lot of control on when an implementation of an abstraction should be instantiated, under which circumstances it can be reused, and something that is often overlooked, when to dispose the instance. Autofac is one of those examples that does this really well. It treats disposables as a first-class concern and assumes that any object that implements IDisposable should be disposed when the (nested) container goes out of scope.

Since the container is already responsible for connecting implementations to abstractions, it can also inject objects that deal with cross-cutting concerns (5). An example of this is a decorator that secretly monitors the calls between objects and which logs warning messages if certain thresholds are exceeded. But I’ve also seen examples such as telemetry collection, exception shielding and dynamic selection of strategies based on the hosting environment.

Then why do some people despise them so much?

The examples I just gave are valid and useful solutions for real-world problems. So then why do certain developers think dependency injection frameworks are such a bad thing? Well, just like Test Driven Development, which can really hurt you if you don’t do it right, misusing a DI framework can cause a world of pain. Something I heard often over the years is the amount of magic such a framework introduces, in particular around the life-cycle of instances provided by the framework. And if you need to know what is the configured life-cycle, finding the original registration can be tedious. If you have just a couple of registrations, you’re probably lucky. But most monoliths I’ve seen contain hundreds of those registrations, resulting in unwieldy bootstrapping code. Especially if types are registered dynamically or when exposing a type through all its public interfaces, it can become next to impossible to find the right registration.

Another problem I’ve heard (and observed first-hand) are the deeply nested call stacks included when some kind of dependency can’t be resolved. Autofac is doing this quite okay, but I’ve seen some pretty obfuscated stack dumps with other framework. You may notice that I keep using the term framework and not library. That’s because most of these libraries don’t behave like libraries. In other words, if you’re not careful, their preverbial tentacles tend to infect your entire code-base. And did I already mention this tendency to introduce Iwhatever interfaces for anything that is used as a dependency. Not something I like to see in my code base considering we try to follow proven practices like Role-Based Interfaces and the Interface Segregation Principle. Not to mention the overzealous faking in your unit tests that usually results from this.

Getting the terminology right

Before we talk about how to do dependency injection the right way, I think I need to first clarify some terminology, starting with Inversion of Control (IoC). This is the process of moving the responsibility for creating a dependency outside the class depending on it. In other words, instead of having the Order Processing module (from the picture at the top this post) new-up a specific implementation of the IOrderRepository, we delegate this to code that creates and/or consumes the Order Processing module. You don’t need any DI framework for this. But since this is the primary job of a DI framework, it’s quite logical that so many people call them IoC containers. In a way, the container becomes responsible for injecting the right dependency into the Order Processing module’s (such as a constructor), hence mixed usage of these terms.

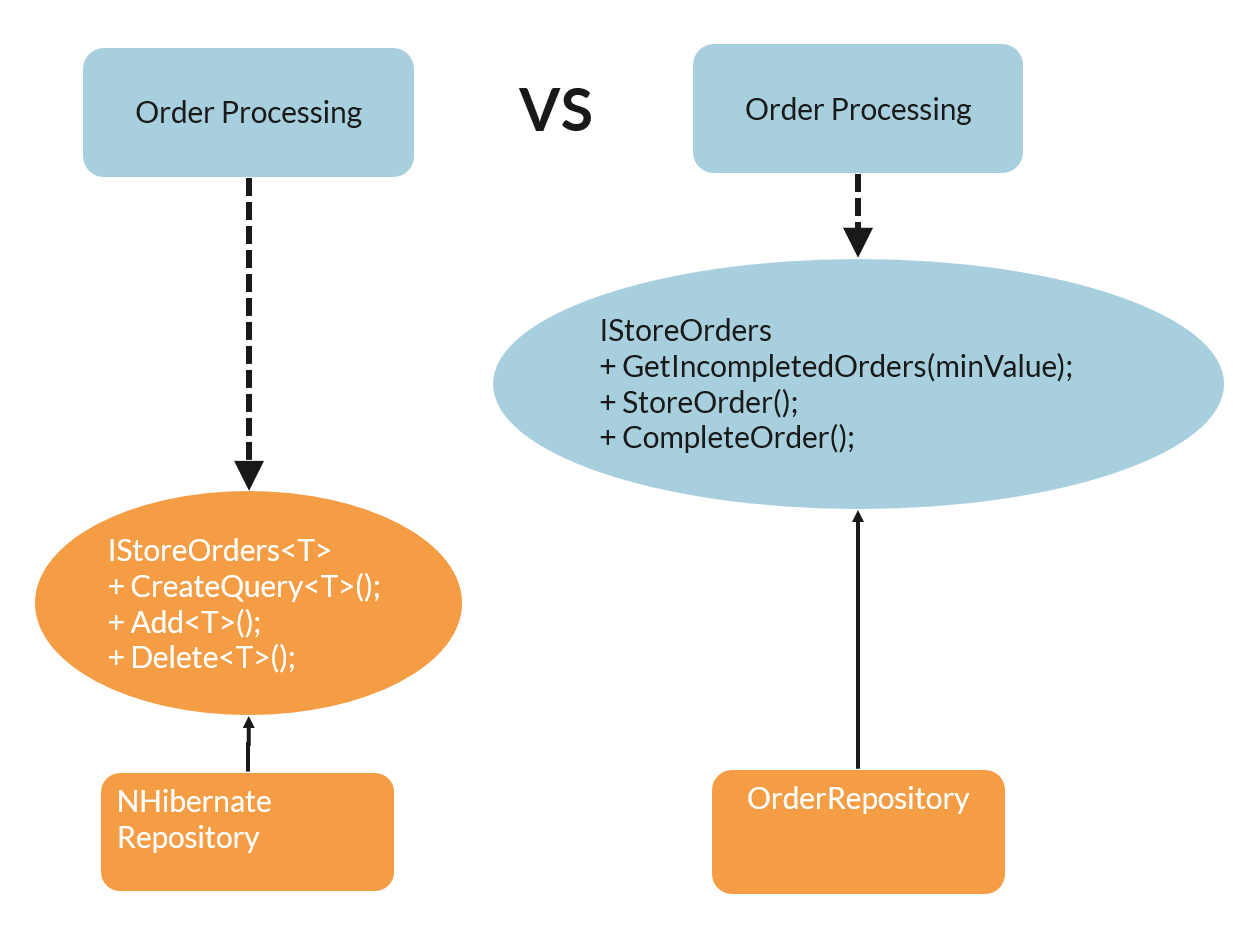

However, a lot of people still think that the ‘D’ in SOLID means dependency injection as well. However, the ‘D’ stands for the Dependency Inversion Principle (or DIP for short), which is orthogonal to the concepts I just explained. DIP talks about reversing the dependency between objects in such a way that higher-level abstractions don’t depend on lower-level abstractions. The idea behind that is that lower-level abstractions tend to be more generic and reusable, and therefor are more susceptible to change. This is also one of principles behind successful package management (which happens to be inspired by SOLID as well). As an example, consider the differences between the left and right side of the picture:

Although they seem to be similar, there’s a subtle difference. The left side defines a pretty generic IStoreOrders<T> interface that is owned by something that probably in the data layer. Based on the name I assume it will define general purpose methods for creating, deleting and querying orders. Notice that the dependency flows from the Order Processing module, a higher-level abstraction, to the IStoreOrders interface, a lower-level abstraction. That also means that the implementation of that interface can’t really make any assumptions about what the caller tries to accomplish. You can, of course, add more functional methods to that interface (such as is depicted on the right side), but that probably means the abstraction will end up having a huge number of methods.

The DIP reverts this dependency by having the Order Processing module define what it needs to function and allowing lower-level layer to implement those. This decouples the module from any low-level details that will change often. This also really aligns well with the Clean Architecture mindset. A nice side-effect of this is that it helps avoiding those dreaded interfaces which are nothing more than the implementing class name prefixed with I.

Doing dependency injection right

Now that we have the terminology worked out, and before reaching any kind of conclusion, let me first share some guidelines on how to do dependency injection in a way that doesn’t hurt you. For instance, static mutable state (anything that is static or behaves like that) is always bad. It causes weird problems in multi-threaded environments, especially now we’re all embracing async and await. Knowing that, it kills me to see that Microsoft has been pushing the Service Locator pattern so much. It is supposed to allow you resolve a dependency using the following statement:

ServiceLocator.Current.GetInstance<IStoreOrders>();

But it’s a static object. Using this in production where all threads will reuse the same dependencies is mostly fine. But just try to switch your test framework from MSTest to Xunit where unit tests run in parallel and each of them is supposed to have their own (faked) instance of a dependency. So don’t use service locators.

Having killed that pattern, the next thing to do is to make sure you only use the container at the root of the dependency graph. In other words, only resolve the root object from the container and never ever take a direct dependency on that container. Let the container handle any dependencies that objects deeper in the graph have. This helps you to treat the container as a library instead of a framework that ends up everywhere in your code base.

What if you need to dynamically resolve dependencies based on a type, key or name? For example, some class in the domain of the system might want to delegate the logic for calculating the discount on an order to a policy, a domain-specific implementation of the Strategy Pattern. Consider this example:

interface IDiscountPolicy

{

float GetDiscount(float originalPrice);

bool AllowsCombiningWithOtherDiscounts { get; }

}

So how would you get the right policy based on the type of order? Just define an abstraction to capture the concept of resolving that kind of dependency. For instance, by defining another interface for this. However, interfaces require you to create fakes in unit tests. So instead, assuming you code in C#, I would probably define a delegate like this:

public delegate IDiscountPolicy GetDiscountPolicy(OrderType orderType);

A parameter typed to that delegate will take any method or lambda expression that matches the signature. A nice side-effect of this is that it allows to avoid container-specific extensions in your production code.

In Autofac (my preferred container), you can use the following registration code to allow somebody to take a dependency on that delegate:

internal class OrderManagementModule : Module

{

protected override void Load(ContainerBuilder builder)

{

builder.RegisterType<SmallOrderDiscountPolicy>().Keyed<IDiscountPolicy>(OrderType.Small);

builder.RegisterType<LargeOrderDiscountPolicy>().Keyed<IDiscountPolicy>(OrderType.Large);

builder.Register<GetDiscountPolicy>(ctx =>

{

var container = ctx.Resolve<IComponentContext>();

return orderType => container.ResolveKeyed<IDiscountPolicy>(orderType);

});

}

}

This registration code or wire-up is part of your production code, so make sure you avoid any kind of deploy-time text-based configuration and include the registrations in your unit tests. Nothing is more annoying than having a suite of green unit tests and then observing the application blowing up at start-up because the registrations were not covered by tests. To keep that wire-up code close to the feature, see if your container supports encapsulating registrations from the example. For instance, the above module can be registered in Autofac like this:

var builder = new ContainerBuilder();

builder.RegisterModule<OrderManagementModule>();

IContainer container = builder.Build();

And since I’m talking registrations here, make sure you keep your registrations explicit. Autofac for example allows you to register a concrete class under its interfaces like this:

builder.RegisterType<SmallOrderDiscountPolicy>().AsImplementedInterfaces();

But this hides the names of the interfaces that this class exposes. It will work at run-time, but trying to find the registration of IDiscountPolicy will become pretty hard if you don’t know where you should be looking. Instead, I also make this very explicit:

builder.RegisterType<SmallOrderDiscountPolicy>().As<IDiscountPolicy>();

Even if your IDE tells you that it can infer the registered interface from the registration code, keep it there. You’ll thank me later.

A question I’ve heard more than often is whether to take dependencies in a class’ constructor, a setter property or somewhere else. My personal advice is to keep the scope of dependency as local as possible. So if only a single method of a class needs that dependency, pass the dependency directly into that method. A common example of this is when such a method needs to get the current date and time. In C#, you can easily do that by de-referencing DateTime.Now. But that’s a static property which can cause the same problems as using a service locator. In most cases, I solve that by defining a delegate for this:

public delegate DateTime GetNow()

With the corresponding registration looking like this:

builder.Register<GetNow>(_ => () => DateTime.Now);

Consider constructor injection if the entire class needs that dependency. But whatever you do, don’t use property injection. It hides the dependency too much and obscures the logic of when that dependency is needed. As a general rule of thumb, a class with more than three dependencies should be frowned upon.

Scoping the dependency does not only deal with constructors or methods. I believe it is important to emphasize that a dependency is supposed to have limited usage. One way to make that clear is to follow the convention that an abstraction such as a delegate or interface should only be used by code that lives in the same folder or any of its sub-folders. It doesn’t protect you from violating that rule, but does help the other developers understand how you envisioned that dependency.

Another way is to use nested containers. Autofac allows you to create a nested scope by calling BeginLifetimeScope on the container interface. This returns a disposable ILifetimeScope that you can use to restrict the availability of a dependency for as long as that scope exist. Depending on how you’ve registered your dependency, you can even allow separate instances per ILifetimeScope, e.g. for each HTTP request. And even if you don’t need nested containers, delegating the responsibility of disposing your dependencies to the container is highly advisable. A mature container is a very advanced and optimized piece of code that is far better at tracking references to objects and understanding when to call it Dispose method. Don’t even try to write your own (unless your name is Jeremy, Nicolas or Steven).

So? Should you use containers or not?

Having covered the good, the bad and the ugly of dependency injection, what remains is to answer the original question of this post. Is an IoC container or dependency injection framework a good thing or not? Well, I think that is a stupid question. Any tool has its merits. Just use it with responsibility. But do you need it? Well, you can avoid the need for a container by composing your system from small well-focused autonomous components into something useful. But that’s usually easier said then done. If you’re in a situation where you need to wire-up dependencies and need to think about the life-cycle of objects and you want to build a loosely-coupled system, then you’ll not some plumbing anyway. And why not use something that is battle-tested, instead of rolling your own poor-mans-container? Sure, you can try the latter if you don’t need anything special. But be honest to yourself and switch to a real container when you need something more sophisticated. I myself prefer to use Autofac at the root of a composed system because its extremely fast, very flexible and allows me to follow my own guidelines. Within components and libraries, I prefer TinyIoc since it’s a source-only NuGet package that doesn’t cause me any dependency pain. But whatever you do, don’t forget the guidelines. They emerged from years of doing the wrong thing. Don’t let history repeat itself.

What about you?

So what do you think? I’m sure this is a very loaded topic, so I’m really excited to hear your thoughts on this topic. Any other guidelines that will help us use our containers more responsibly? Let me know by commenting below. Oh, and follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for better solutions.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment