A Git collaboration workflow that provides feedback early and fast

At Aviva Solutions, we’ve been using Git for a little of over two years now and I can wholeheartedly say that after having worked with TFS for years, we’ll never go back… ever. But with any new technology, practice or methodology, you need to go through several cycles before you find a way that works well for you. After we switched over from TFS, we kept kind of working in a centralized fashion (hey, old habits don’t die) where all those feature and team branches are kept on the centralized repository. If the entire code-base involves only a couple of developers, all is fine and dandy. But if you’re working with 20 developers, not so much, unless you love those rainbow-style historical graphs…

So after a couple of months, in order to achieve a bit more isolation and less noise, the first teams started to fork the main repository. This worked quite well for most of the teams, in particular due to the power of pull requests. But it took more than a year before we managed to coerce all teams into doing that. That may surprise you, but teams get a lot of autonomy. For instance, they decide on their development process (Scrum, Kanban or a hybrid of that) or the way they work together. But switching from the nicely integrated combination of Visual Studio and TFS to the hybrid of command-line tools and half-baked desktop apps proved to be harder than I expected. Apparently the concepts of clones, forks and remotes were not as trivial than I thought.

We couldn’t just revoke all write-access and force teams to work on forks without causing a riot. So it took another six months until we finally got all teams to agree on a process where everybody works on forks and uses pull requests (PRs) to submit their changes for merging by a small group of gate keepers. Teams use the PR for getting build status updates, tracking test status and performing code reviews by their peers and technical specialists. The gate keepers don’t do code reviews themselves. They just make sure the code was reviewed and tested by the proper people. This has worked quite well for the last 9 months or so, but what about teams? How do developers within teams work together on their shared tasks and user stories?

Now that people can’t directly push to the central repository anymore, they have no choice than to use a fork to do their work. We use GitHub, which does not have the concept of a team fork, so most teams use the fork of the first person that started working on a particular task. All developers involved in that work get write-access and can directly push to that repository. Most teams seem to be fine with that and I myself have worked like that as well. But in my experience, this approach has several caveats:

- Code only gets reviewed when the combined work of the involved developers gets being scrutinized as part of the final pull request, which means the rework comes at the end as well. And if you value a clean source control history, it’ll be very difficult to amend existing commits and result in those dreaded “Code review rework”.

- The changes being pushed by the individual developers can break the shared branch, e.g. by pushing compile-errors or failing unit tests. Even if that shared branch is linked to a WIP (work-in-progress) pull request, your build system might not be fast enough to trigger the team. They might be spending half an hour trying to figure out why their code doesn’t compile, only to discover they pull a bad commit from the other team member.

- A developer might push a solution that doesn’t align with the agreed solution for the involved task. But if the other devs don’t need to look at that code up until the final code review, the rework might be substantial.

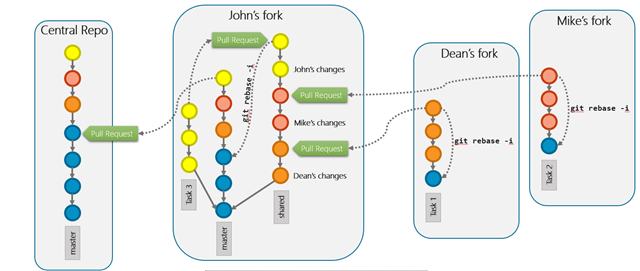

That feedback loop is a bit too long for my taste. So we’ve tried an approach which probably could be best described as a multi-level pull request flow. It looks like this:

The idea is simple. Everybody works on their own fork, but there’s a single branch on one of the designated forks that serves as the integration point for each other’s changes. So in this example, the shared branch is on John’s fork and neither of the three will write directly to the branch. Whenever Dean has completed his task, rather than writing directly to the shared branch, he’ll issue a pull request to John’s fork. This PR is then used to do an early code-review by either Mike or John, after which Dean will do the rework on his branch. Since this team values a clean history, Dean will complete his task by cleaning-up/squashing/reordering the commits on his branch using an interactive rebase. As soon as this has been done and the involved builds report a success status, John or Mike will merge the PR. Obviously, Dean and Mike follow the same work flow.

When all collaborative work has been completed, one of the guys will rebase their work on the latest state of affairs of the central repository and file a pull request to it. If not all earlier mentioned pull requests were merged using GitHub’s new squashing merge technique, an (interactive) rebase will get rid of those noisy merge commits. Granted, that final PR might still receive some code review comments. But if you have been involving the right people in any of the earlier PRs, that should be minimized. Again, the goal is to keep the feedback loop as short as possible.

What do you think? Did I tell you something you didn’t know yet? And what about you? Any tips to add to this post? Love to hear your thoughts by commenting below. And follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for better solutions.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment